What are Floaters?

Floaters are shapes that people can see drifting across their vision. Floaters are small bits of debris floating in the vitreous jelly inside the eye. They can come in a variety of forms such as small black dots, short squiggly lines or even large cobweb shapes. Shortsighted people tend to suffer from them more and they increase, as we get older.

What causes Floaters?

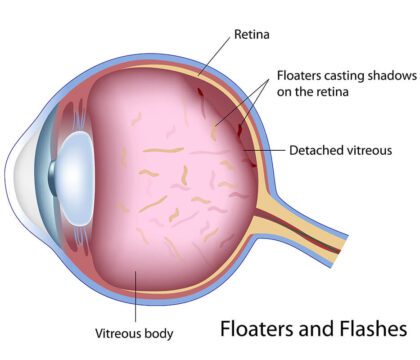

The eye is filled with a jelly like substance called vitreous. The vitreous sits behind the pupil and lens. The jelly is made mainly of water with a meshwork holding it together. As we get older, a process known as vitreous syneresis occurs; the meshwork breaks down and lakes form. The solid portion of the gel forms debris. The debris casts shadows onto the retina, which we see as floaters.

In 70% of people, by the age of 70, the liquefied vitreous gel can lose its support framework causing it to collapse. This process is known as a posterior vitreous detachment (PVD). As the vitreous gel peels away from the retina, it can cause people to see intermittent flashes of light. The flashing light will usually subside over 4 to 12 weeks, but in some patients it may take a little longer. When a posterior vitreous detachment occurs people often become aware of a cobweb or net curtain-like floater that can be quite intrusive at first.

Inflammation in the eye is a rare cause of floaters.

What complications could occur?

In the vast majority of cases floaters are harmless and represent the normal, natural (although occasionally annoying) aging change of the eye. They usually become much less obvious with time as the brain adjusts to the change and eventually filters them out.

Very rarely during the development of a posterior vitreous detachment, the vitreous gel can be stuck to a patch of retina and cause a tear. If the seal of the retina against the back of the eye is broken, fluid can start to track in behind the retina causing it to detach from the back of the eye a little like wallpaper peeling of a wall. This uncommon event occurs in approximately 1 in 10,000 of the population in general. Usually, if a tear develops in the retina people experience a very marked shower of floaters associated with flashes of light in their peripheral vision. The light is usually persistent and occurs in daylight. Some people notice a curtain effect coming in from their peripheral visual field. This requires urgent attention by an eye doctor.

Treatment options

Since floaters do not harm the eye, and in the vast majority of people, they do not cause a significant problem, we generally do not recommend any form of treatment for them. Dark glasses can help make floaters less obvious in the meantime. People with floaters that cause persistently disabling impairment of eyesight may benefit from surgery.

It is possible to carry out an operation to the eye to remove the vitreous gel (vitrectomy), which will also remove the floaters. Very occasionally, this course of treatment is useful in people with very severe floaters or in those who cannot adapt to them.

What are the likely benefits of surgery for floaters?

Surgery offers the likelihood of a substantial improvement in eyesight in 9 out of 10 people with severe floaters caused by vitreous separation. A small number of floaters may persist.

Can floaters recur after surgery?

Floaters caused by age-related vitreous separation are not expected to recur.

What are the risks of surgery for floaters?

Vitrectomy surgery predictably causes progressive cataract (clouding of the eye’s natural lens) within two years. Cataract typically results in progressive myopia (short sight), glare and clouding of vision, but can be managed by surgery to replace the clouded natural lens with a clear lens implant.

All surgery inside the eye carries a risk of harm from side effects including raised eye pressure, inflammation, detached retina (2 in 100), bleeding and infection (1 in 1000). These effects can usually be managed effectively using medication or further surgery. The risk of lasting harm to sight, comfort or the eye’s appearance despite further treatment is up to 5% (1 in 20).

Most people decide against surgery in view of the risks. For a small minority of people who have persistently disabling impairment of sight, the potential benefits of surgery outweigh the predictable side effects and the risk of lasting harm.